Share

Understanding the pain system is the first step to managing it.

Brain and pain science has been advancing rapidly. If you have chronic pain there is a benefit to keeping up with new developments. Research shows that self-education is an important step in managing pain.

Brain and pain science has been advancing rapidly. If you have chronic pain there is a benefit to keeping up with new developments. Research shows that self-education is an important step in managing pain.

Current understandings are summarised here and will be updated as new advances come to light.

1. The purpose of the pain system is to protect the body.

The pain system is designed to deliver warning signals to the brain to alert you to do something to protect body parts that the brain “thinks” are threatened or about to be threatened. This occurs in acute pain. Acute pain is short-term and does not persist for very long. Chronic pain is a different condition. It is when pain persists longer than expected due to an imbalance in the pain system.

2. The experience of pain is shaped in the brain.

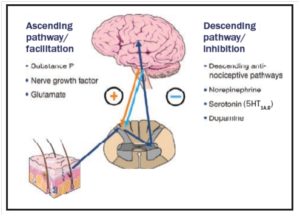

When a body part is stressed by pressure, temperature or inflammation the nerve endings are stimulated to send signals to the spinal cord. The signals are then relayed upwards to the brain. There are multiple pathways in the brain that “compute” whether these signals are to be neutralized or amplified depending on how the danger of real or potential tissue damage is assessed. Every human brain is unique. As a result, no two brains will respond to the signals or sensations in the same way.

Therefore the brain’s experience of pain intensity whether high, low or somewhere in between is not necessarily an accurate measure of the amount of tissue damage. How we experience pain is an integrated response to all the information collated from all areas of the brain. Some of these areas govern emotions, perceptions, anxieties, mood, past memories, and future intentions. One well-documented example of this process is the experience of pain during childbirth. Emotions, past experience, social culture and memories are known to shape the pain experience which is unique to each woman. Similarly, in arthritis, back pain, migraine, fibromyalgia etc, the pain experienced by an individual is unique and shaped by their brain.

3. X-rays, ultrasounds, MRIs do not measure pain.

Taking an x-ray or MRI to determine the cause of pain is like taking a photo of a car to determine how much petrol is in the tank. The xrays are showing the structure of a body part and not the nerve signals that can fuel the experience of pain. Numerous research studies have proven that there is no association between the appearance of a body part on a x-ray or MRI and the pain that is experienced. An individual can have a very abnormal looking spine on a scan and yet have no pain. Another individual can have a very normal looking scan yet have high levels of pain and disability.

How can you have a very abnormal looking spine on x-ray and no pain? This is because the brain does not register this change in the shape of the spine as a threat or a warning signal. Perhaps the changes occurred so slowly over time that the brain did not register any need for urgent action.

Another example is phantom limb pain. In this condition even though a part of the limb is missing, the brain still registers ( “remembers”) the pain in that part. It is as if the brain and/ or the spinal cord relay station has “its wires crossed” and this literally might be true.

4. The brain often “thinks” the body is in danger even when it is not

An example of this situation is a condition called fibromyalgia. In this condition, whole body pain is experienced when there is no tissue injury or damage. This condition is often associated with other symptoms of brain sensitisation such as poor sleep, sensitivity to temperature, headache, irritable bowel and bladder and fatigue. This does not mean the pain is a result of psychological processes and not “real”. This is an example of an imbalance in the way the brain receives the signals and processes them as pain.

In the well-functioning pain system, the brain has the ability to increase, neutralise, or dampen the signals it receives. This is done via over 600 specialised descending nerve pathways that travel from the brain to the spinal cord and either facilitate or inhibit the ascending signals.

In fibromyalgia, it seems that the main area of imbalance in the pain system is with the “malfunction” of these inhibitory pathways.

Similar maladapative processes are thought to be the cause of many chronic painful conditions.

5. Experiencing pain can sensitise the brain.

In the new scientific field of neuroplasticity, it is recognised that brain neurons grow or shrink depending on how much they are used. When the brain pain pathways are constantly activated they grow resulting in an exaggerated and faster response. In the context of pain, it means that the more we experience pain, a smaller stimulus may be required to trigger the response.

6. Pain can be triggered by factors unrelated to physical harm

6. Pain can be triggered by factors unrelated to physical harm

One of the most painful experiences is having the dressings changed in someone who has had burns to their body. These dressings need to be changed regularly. It is well recorded that individuals have increased pain immediately on hearing the dressing trolley being wheeled into their room. The brain associates the sound of the trolley with pain. Just thinking about the procedure and the expectation of pain can increase the experience of pain. Another example is back pain, work stress and anxiety. When the stress levels increase the experience of pain can intensify. There are well-recognised nerve system and brain hormone pathways that cause this biological response. This is not a psychological response.

It is recognised that emotional states such as anger, depression, and anxiety are known to adversely influence the experience of pain. Although it is hard to believe, research provides strong evidence that a significant aspect of chronic back pain is determined more by emotional and social factors than by actual physical damage to tissues. Once pain has gone on for more than 3 months it is more likely to be due to brain pain processes than to ongoing damage to the tissues.

7. The brain can alter its sensitivity level to pain

The brain can increase or decrease its sensitivity to a painful stimulus from the body in many ways. In an emergency situation, the brain is so focused on survival the pain signals are inhibited and do not get through to conscious awareness.

When the brain and the spinal cord ( central nervous system ) becomes sensitised, the pain will be experienced sooner and more strongly, so that even normally innocuous mechanical pressures can cause pain.

There is a lot known about how the brain adjusts the level of sensitivity to nerve signals but there is much more to discover. This process is not static and there are adjustments being made to the brain/pain “volume switch” constantly. For many individuals with chronic pain, the “volume” has simply been turned up too loud and left on for too long. This is called central sensitisation, and this process plays a prominent role in many chronic pain states. It is another example of how chronic pain does not necessarily imply continuing or chronic harm. An excellent lecture by one of the world’s leading researchers, Dr Dan Clauw can be viewed. Here is a link to this lecture.

Conclusion

Pain is a very complex brain-body process. The pain experience needs to be evaluated separately from any presumed tissue injury.

Understanding this reduces anxiety and stress which generally makes pain worse. It also means that an essential part of treatment is to focus on adjusting brain pain system processes. This can be done by applying strategies that encompass a whole person approach.